Data Practices for Open Science – 3 Quick Tips

Sir Isaac Newton said, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” As scientists, we aim to share our findings with colleagues who may use the information to continue to make progress on important questions. Making your data more transparent and reproducible not only contributes to a more useful body of work but provides “shoulders” for those who come after you (other colleagues, students, and collaborators). It’s also handy for improving your own workflow. Your personal peace of mind is another added bonus to front loading the work of organizing and describing your dataset.

You might be wondering what are we referring to when we talk about “Open Science”. A more open approach to research means making results accessible for the benefits of both scientists and broader society (UNESCO 2023). The Open Science movement aims to increase transparency and the speed of knowledge transfer. Barriers to Open Science include things like: paywalled journals, favouring knowledge produced by high-income countries, hidden or unknown source code or workflow, and supporting data that is unavailable or unusable. In this article, we’ll tackle the last barrier and talk about practical ways to make your data more Open.

1. Use a tidy format

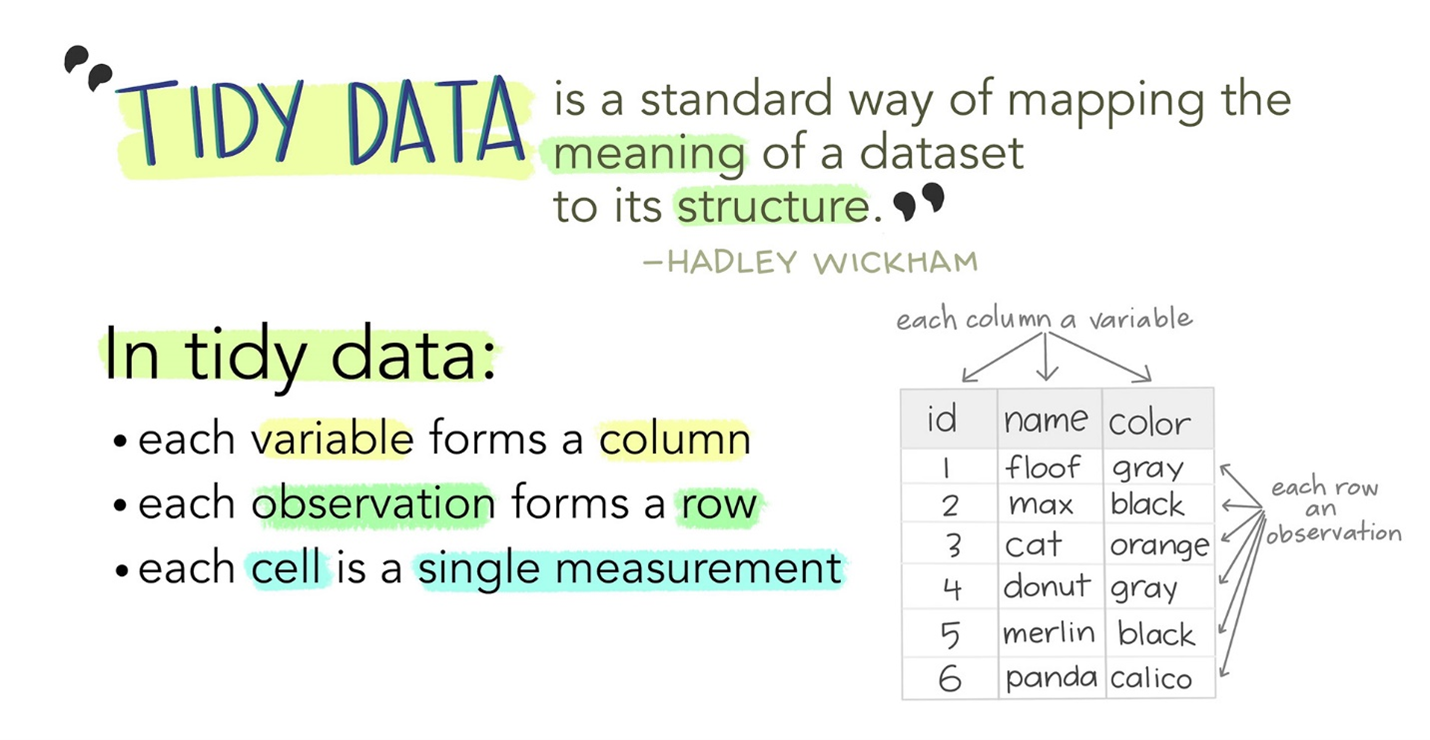

Illustration from Tidy Data for reproducibility, efficiency, and collaboration by Julia Lowndes and Allison Horst. Adapted from Wickham (2014).

Illustration from Tidy Data for reproducibility, efficiency, and collaboration by Julia Lowndes and Allison Horst. Adapted from Wickham (2014).

For an excellent introduction to Tidy Data, check out Hadley Wickham’s 2014 paper in the Journal of Statistical Software (Wickham 2014). The tidy approach to data dictates that when organizing data, every observation should be represented by a row and every variable a column. This is a great approach for standardization and machine readability.

2. Redundancy in data is OK sometimes!

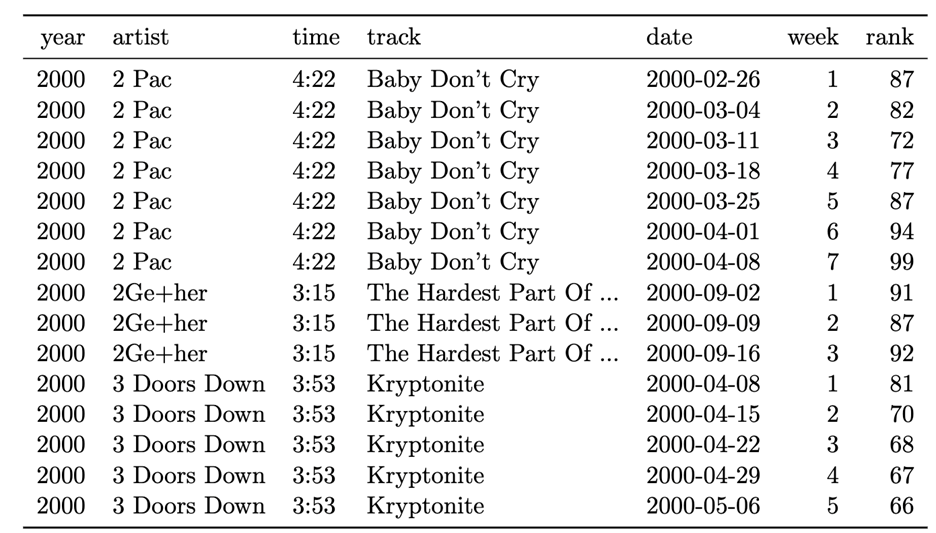

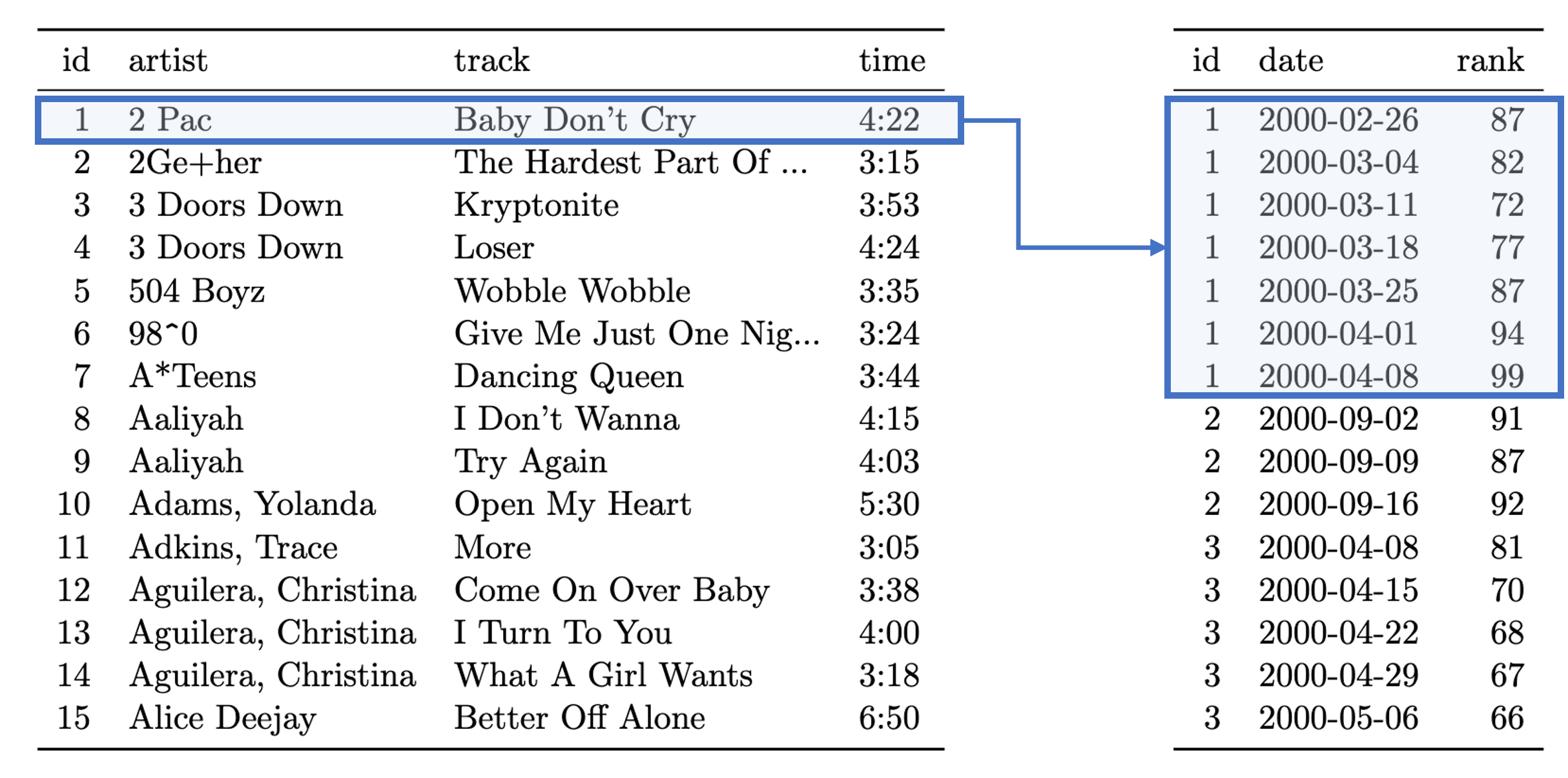

Throughout our scientific careers, we’re often told to be concise and simplify so this advice may surprise you. Strategic redundancy in data allows you to make linkages between different pieces of information. It also saves space. One way to invoke the hidden power of redundancy is using metadata and data dictionaries to link important context to your primary dataset. For example, this table contains two types of observations: song information and Billboard rankings with one entry (i.e., row) each week the song remains on the Billboard Hot 100. Look what happens when we split the information into two tables: one with the song titles, artists’ names and run times; and the other with details on their Billboard rankings. This:

- Avoids confusion at scale – note how there are two types of temporal data in the first table. One could conflate time and date.

- Saves space. Say there were 100 songs with an average of 7 entries each. Rather than a table with 700 entries and 7 variables (4900 pieces of data), you now have 2 tables (containing 4500 data points total). This difference in memory usage scales with the size of your dataset.

Table 1. Too much information at different scales crammed into a single table. Table adapted from Wickham (2014).

Table 1. Too much information at different scales crammed into a single table. Table adapted from Wickham (2014).

Table 2: Example of using redundancy by splitting tables in two. Note how one song (left) has multiple Billboard rankings (right). Tables adapted from Wickham (2014).

Table 2: Example of using redundancy by splitting tables in two. Note how one song (left) has multiple Billboard rankings (right). Tables adapted from Wickham (2014).

3. Keep raw data raw

Separating your raw data from analyses is essential for reproducibility. After all, how can we reproduce an analysis if we have no access to the original dataset? In repositories, create a folder named RAW. Place unmanipulated data here. Do not open these files except to add or remove raw data. You may consider setting them to “read-only” when viewing in Excel. Keep all analyses in your scripts and outside of Excel, which will read the data and create outputs from it. Use a descriptive file name for any outputs generated from raw data and place them in a separate folder.

Embracing Open Science practices doesn’t have to be overwhelming. By adopting tidy data formats, allowing for strategic redundancy, and keeping raw data untouched, you can contribute to a more transparent and collaborative scientific community and yourself up for smoother workflows and more reproducible research. These small, intentional steps can have a big impact, helping others build on your work and accelerating the pace of discovery.